A perfect presenter for A Perfect Planet

05 March 2021Rejection, deception and jealousy will not deter 3 ingénue heroines from fighting for love in 3 brand-new telenovelas coming to DStv in March

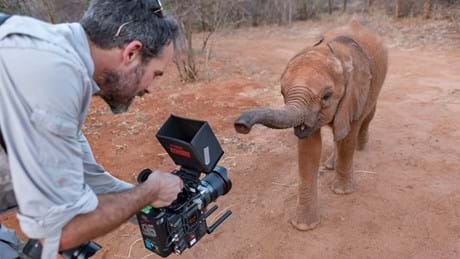

A Perfect Planet’s cinematographers went to the ends of the Earth to capture the documentary’s jaw-dropping scenes, live and in person

Whether they’re climbing down into a volcano, presenting themselves as a snack in an area where hungry bears have just come out of hibernation, knee-deep in hot mud in the middle of nowhere, or down on all fours to get that perfect shot, the cinematographers of the documentary series, A Perfect Planet, have a special breed of determination. The result? Breath-taking footage that drives home the point that our beautiful planet and its complex web of life are a source of wonder that's well worth protecting.

Their work behind the scenes is every bit as fascinating as the footage they shot, and on Sunday, 21 March, we’ll see a very special sixth episode all about how A Perfect Planet was filmed. But if your curiosity has already been piqued and you simply can’t wait, here’s a sneak peek at what some production members had to say, including Producer Huw Cordey, Cinematographer Matt Aeberhard, Cinematographer Justin McGuire, Associate Producer Emily Frank, Producer-director Ed Charles and Producer-director Nicholas Shoolingin-Jordan.

A Perfect Planet airs on BBC Earth (DStv channel 184) exclusively on DStv Premium.

Watch BBC Earth Watch A Perfect Planet Upgrade to Premium

In the weather episode, a little desert rain frog in Port Nolloth resembling a marshmallow has captured everyone’s hearts. It’s one of producer-director Ed Charles’s favourite sequences from the whole series. Bringing it to screen was the job of South African-born, Vancouver-based specialist camera operator Justin Maguire, and it was a test of his patience.

“How do you find a frog in the desert? With difficulty,” Justin admits. “While we were there, the country was right at the end of a very dry spell. Three years of incredibly dry weather. We didn’t see or hear a frog for 5 days. At that point, we had a shoot (planned) of two-and-a-half weeks, and not seeing your key animal that quickly… the scientists we were working with thought that was probably the worst record for finding these frogs and they were really nervous. It was a slow process.

“It’s a good example of how animals are so in tune with the weather and rely on it. Their behaviour is dictated by it. When it’s dry and not the ideal conditions, they just stay underground where they are protected. We were fearful that we might not even see enough frogs to film. Then we had a change of weather conditions and the coastal mists started to thicken and come in and we heard that first, distinctive call of a rain frog and found our first frog with much celebration. They become endearing when you get to know them.”

It wasn’t enough to have found just one frog though. “We don’t want to stress the animals. We have a policy when we’re filming that we wouldn’t film the same animal for more than 48 hours,” Justin explains. “A lot of our time was spent looking for individuals in different areas and making sure we were using different individuals. The story is a narrative of one animal, but as we’re aware of their wellbeing, we filmed a number of animals that were doing different things over that time,” says Justin.

“It’s about finding a real, emotional story that has an intimate connection to a character. That’s generally what I try and do. Look at what story you’re telling and how you can engage people in that story. And then film it in a way that delivers that engagement, where you feel like you’re with an individual, like a hero's journey.”

Aside from finding his frog, Justin faced the usual challenges of working in the field. “Some trips I’d just love to be spending more time in the location with the animals and the people that I’m with. On other trips, you’re getting bitten by bugs and you’re waking up at the worst hours, and it’s cold or hot or humid and you are so thankful to leave wherever it is,” he says.

Keep an eye out for: In the Oceans episode, there is a sequence with a bait ball filmed by South African cinematographer Roger Horrocks. “He’s been filming bait balls for years,” says Ed. “And he says it’s the most intense one he’s ever seen. It was the most dramatic, the most energetic, high-octane, with dolphins and gannets, and sharks coming in.”

Cinematographer Matt Aeberhard went the extra mile to film flamingos at Lake Natron for the Volcanoes episode.

“The soda flats themselves are pretty inaccessible. Up until relatively recently, more people had landed on the surface of the Moon than had stood amongst the flamingos in the middle of the Rift Valley, so it's special,” he says.

“Every trip to the flats is an expedition. It was described by a famous East African ornithologist named Leslie Brown as the foulest place on Earth. But he loved it, as I do. The beauty there could be considered to be a mirage because underneath it all, there is this highly caustic environment. The pH of the soda flat at its most highly concentrated form is about 12, which is not far short of household bleach. Added to that, the temperatures of the muds can reach the temperature of, let's say, a scalding cup of tea. It's a thick, gooey, sulphurous mud. It's sticky getting out there. The mirage at the lake makes it dangerous for helicopters and light, low-altitude aircraft to fly in the vicinity of Natron, so really, the only option to get out there is via hovercraft, which is fun, but that has inherent risks in that the skirt of the hovercraft – the rubber skirt that contains our lift – is shredded up by the soda crystals that are jagged, like shark's teeth. And as you're out on the flats, that gets a little worrying. You're always hoping that you don’t get a blow-out and lose the lift because that could see you stranded in a pretty inhospitable place where helicopter rescue is really your only solution. Leslie [Brown, the ornithologist] tried to walk it in the 1950s and didn't get very far – he almost died in the attempt. The soda crystals cut into your legs and burn your legs with soda alkalis and cause sores. Mine have only just healed, really, after months of dry air.”

“It's a cool place to work. The hovercraft is really just a delivery vehicle to the flats and once you're there because you don't want to disturb the birds, you set up hides and blinds, which you sit in all day. To access them, we go really early in the morning under the cover of darkness and have to wear snowshoes to get to the blind to negotiate the mud, which actually doesn’t look that strange because Lake Natron, when you're out on the flat, is white, almost like a crazy snowscape. But it's dehydrating, and it's exhausting work. When you come back from the flats, what usually happens is that the wind picks up, so you get covered in this salt spray, this caustic salt spray, and air-dried by it. The salt gets everywhere, it gets in your clothes, it gets in your face, it gets in your hair, your hair inevitably ends up being spiked. If you can imagine the ghost of Sid Vicious, that's what you look like when you get back. The only way of cleaning yourself is to take a luxurious bath in hot springs, where you get exfoliated by the tilapia fish in the hot springs.”

Associate Producer Emily Frank adds, “There was one sequence that Nick [producer-director Nicholas Shoolingin-Jordan] filmed in the Sahara Desert (for the Sun episode) and it was so hot on the sand, filming tiny little ants, that the camera actually stopped working. Nick joked that the cameraman was so hot that he just couldn’t focus on things. They ended up using a solution which one of their local guides recommended, which was to wrap a wet piece of white cloth around the camera and around the cameraman, and that, combined with the desert winds, cooled the camera right down so it could work again. It cooled the cameraman down, too. You have to work in all different weather conditions.”

Under such extreme conditions in such remote locations, the series producers did their utmost to avoid situations in which they’d hurt a camera operator.

“Anyone who makes films for the BBC knows that we spend a huge amount of time looking at the health and safety risks of every single place that we want to try to film,” says producer Huw Cordey. “We have a particular responsibility when we are out in the field because some of these places can present a lot of hazards. We fill out very, very detailed health and safety forms before we go off, and it's signed off by multiple people. We really think hard about all the dangers. We are all medically trained, so we look at the worst-case scenario and make sure we have a flow of what would happen, how we would get a patient out. It can be a long and difficult journey. So the best thing is for injuries not to happen in the first place. Accidents are unbelievably rare. We were very careful most of the time.”

But while nobody was bungee-jumping out of a helicopter to get that perfect shot, there were a couple of slips.

“We did have one small accident on the shot,” admits Huw. “We were filming on Kamchatka (in the Russian Far East, for the Volcanoes episode) in the valley of the geysers, an area where there's lots of different thermal pools and explosions of boiling water. We were filming brown bears around these geysers. The brown bears come out of hibernation, and because this valley where all these geysers are is very, very warm, there's no snow, so there's lots of grass to eat, so the bears come out and it's their first meal of the season. And you can get very, very close to these bears, they pretty much ignore you. It's an amazing place.

“Unfortunately, our lovely Rolf Steinmann, a German cameraman – it's just one of these things – he stepped back into a boiling pool of water and severely burnt his foot, which was pretty nasty. Being a very tough cameraman, he carried on for about a week, but he did end up having a skin graft and being on his back for 4 weeks. Just one small accident stepping back and those were the consequences.”

Huw puts it in perspective: “In my 30-year career, incidents like that I could count on one hand. Probably the most hazardous thing that any of us ever do is to go in a car. It's misleading to feel like the real dangers are in the middle of nowhere in a remote place. Some of the things that we do on a daily basis are just as dangerous.”

Nick adds, “They're very rare indeed. The only thing that really comes to mind is we were filming Arctic Wolves in Ellesmere Island, which is only 500 miles from the North Pole. No one had ever gone there in winter because it's difficult. The preparation that went into the filming of that story was immense, and one of the things we know was very difficult was travelling by Ski-Doo (snowmobile). You get a windchill of -50, -60 (Celsius), so every inch of your face has to be covered with a balaclava, just your eyes showing. On one of the long trips to look for the wolves, Kieran O Donovan, our Assistant Location Director, had a tiny little bit of skin showing. He didn’t even notice it. And by the end of the journey, he had a little patch of frostbite. He was fine, he took a few days off and healed up. He still has a little scar. That's just how vital your clothing and preparation is. If the team hadn’t taken such stringent precautions, you can very quickly go into a territory where you lose fingers and toes to frostbite. So we do prepare incredibly well.”

Producer-director Ed Charles adds, “We went to film wild camels in the Mongolian Desert in the middle of winter, which is when they do their breeding behaviour. It would drop down to -40 at night, and there are very strong winds blowing across there. We were in the middle of nowhere, we must have been the only people for 100,000 square miles (258,998 square km). So if anything went wrong there, it's not like you can just drive out and go to a hospital. Any med-evac would have taken 2 or 3 days. We had to be super careful. It's -40 at night, -20 to -30 during the day, so you need to be dressed accordingly.

"But more than that, you can’t even break an ankle or something because it's going to take you at least 3 days of very involved medical evacuation procedures and helicopters to get you out of there. You have to be sensible, be careful. You plan for your risk assessment and then you act out your risk assessment accordingly.”

The environment had its dangers, but there was a touch of magic in meeting some animals that seemed to only be curious about the crew. When Rolf Steinmann (the German cameraman who stepped in boiling water) was filming the Arctic Wolves in Ellesmere Island (for The Sun episode), he had massive Arctic wolves coming right up to him for a sniff. Ed says, “He was filming in the polar night, before the sun had really even risen. And what’s incredible about those wolves there is that it’s such a remote place that they’re not really used to humans, so they have no fear of them, which you might think would be scary, but to be honest, they’re just inquisitive. There’s a fantastic photo that someone took of Rolf, of him kneeling by the camera and this huge grey wolf just sat within 2 or 3 metres and they’re just looking at each other. No threat, no danger at all. Just pure inquisitiveness.”

DStv in association with BBC Earth will be hosting a Watch & Win Competition offering viewers the chance to win A Perfect Planet book. To be eligible to enter, participants must watch BBC Earth (DStv channel 184) on Sundays at 16:00 or on Catch Up, then answer the questions posted weekly on this webpage.

BBC Earth is also giving one lucky couple the opportunity to experience the beauty of Tanzania! Simply sign up for DStv Rewards via the MyDStv app or the DStv website and enter the BBC Earth competition. Click here for more information.

A Perfect Planet airs on BBC Earth (DStv channel 184) exclusively on DStv Premium.

Watch BBC Earth Watch A Perfect Planet Upgrade to Premium

For more behind-the-scenes details, you can see Pearl Modiadie’s discussion with the filmmakers here.

Watch A Perfect Planet S1 from Sunday, 14 February, on BBC Earth (DStv channel 184) at 16:00. The series is available on Catch Up.

BBC Earth is available on DStv Premium. To upgrade your package or to get DStv, click here.

No dish? You can stream A Perfect Planet with the DStv App